Share

Image by PISTON

Amidst the scorching heat of last April, an elderly jeepney driver, diligently navigating one of the city’s most congested streets, expressed deep concern about the impending jeepney phaseout. “They are always siding with the rich. What will then happen to us?” he said, thinking about potentially losing his only source of livelihood.

In 2017, the Department of Transportation launched the Public Transport Modernization Program (PTMP) to “transform the public transport system in the country, making both commuting and public transportation operations more dignified, humane, and on par with global standards.” Under this program, traditional jeepneys aged 15 years or older will be phased out and replaced by electric-powered or Euro-4-compliant vehicles. Moreover, individual jeepneys are required to consolidate into a cooperative or a corporation.

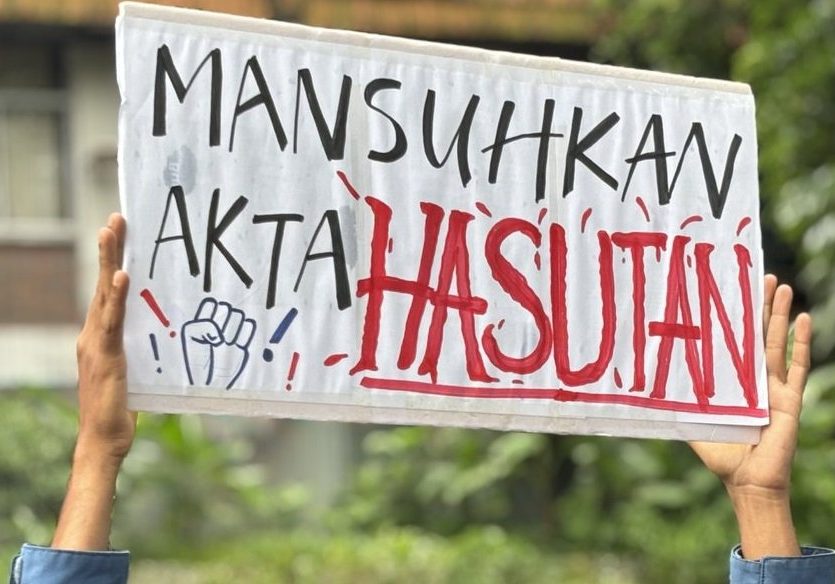

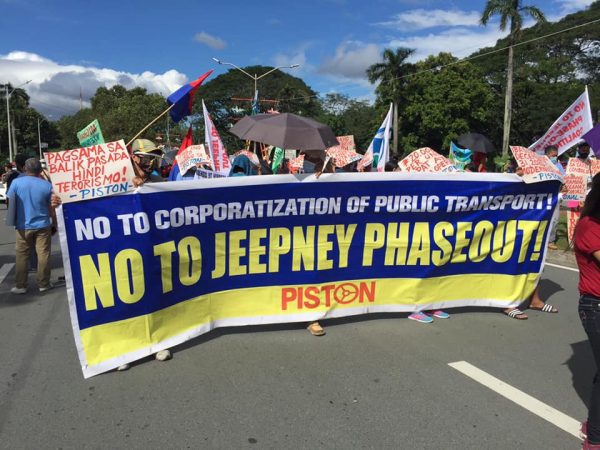

The phase-out could have happened on 30 December 2023 if not for strong pushback led by the Federation of Public Transport Groups and Associations in the Philippines (PISTON) and Manibela, forcing the government through its implementing agencies, the Department of Transportation (DOTr) and the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) to reconsider the deadline. This was followed by filing a temporary restraining order (TRO) with the Supreme Court “to prevent the grave and irreparable injury that the petitioners, the jeepney drivers and operators, their families, the commuters, and the public, in general, will suffer.”

The phase-out finally took place on 30 April 2024, and 15 days later, apprehension and impounding of unconsolidated traditional jeepney units began. Meanwhile, PISTON and Manibela are still knocking on the Supreme Court’s door to act on its petition for a TRO against the PTMP. The modernization debate continues. The situation is precarious, and the future of the jeepney drivers remains uncertain.

Where is the ‘public’ in public transportation?

Following the Paris Agreement, which the Philippines is a signatory, countries have committed to substantially reducing global greenhouse gas emissions. In the Philippines, a study by TRANSfer found road transport to be the largest contributor to air pollution and energy-related Greenhouse gases (GHG). On top of this is the notoriety of the entire public transportation system, driving the volume of private vehicles, thus placing Manila among the cities in the world with the longest commute.

In the face of the transport and more significant climate crises, no one disputes that the Philippine government needs to act immediately. While some improvements in road and transportation infrastructures can be observed in recent years, the government always seems to miss the mark regarding people-centered mass transportation systems. The ownership structure of most train lines, buses, and highway systems in the Philippines is shared by the government and private corporations in either maintenance, operations, or both. Regardless, private investors are protected by sovereign guarantees in the event of profit loss, with Filipino taxpayers shouldering these losses. Investors can also influence how these infrastructures are built, which often benefits their own malls, real estate areas, and commercial or residential buildings.

At 13 PH pesos (0.21 euro) minimum fare, jeepneys are considered the ordinary Filipino’s primary mode of transportation. Post World War 2, leftover military jeepneys were transformed into public utility vehicles and earned the title “king of the road.” Jeepneys stand out on the road with its often quirky and colorful drawings and decorations. When tourists arrive at the airport, they are greeted with a replica of the jeepney, which proves it is an iconic symbol of Filipino culture. It has routes on smaller streets, making it a regular fixture of a typical Filipino neighborhood. Getting a jeepney ride may be challenging during rush hours, but it is dependable and affordable for regular commuters, especially minimum-wage workers and students. It is something that the wealthy and out-of-touch political elites can never grasp, unraveling the class struggle embedded in this modernization program.

The PTMP has effectively polarized the public into taking sides: the government or the jeepney drivers, the environment, or the jeepneys. Among the sentiments pointed to is jeepney drivers’ refusal to accept change or hard-headedness, as driving jeepney has been their only known means of livelihood. While it is true that many of the jeeps are inherited and the profession is passed down through generations, dismissing the drivers’ position against modernization as mere sentimentality does not help in advancing the modernization debate. It even pushes it further from the real issue. Thus, it begs such questions: who stands to gain, and who stands to lose? Whose interests will advance, and who will be left behind? Whose rights and dignity should be sacrificed to achieve a sustainable future?

A recent study by the University of the Philippines Center for Integrative Studies indicates that the concept of a just transition is currently being co-opted by governments and corporations, diluting its transformative agenda.. The study examines the experiences of selected jeepney operators in Bacolod City, located in the Negros region. It argues that the Public Transport Modernization Program (PTMP) places too much emphasis on technological solutions, which the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) considers inadequate. According to the study, this approach will only worsen the vulnerabilities of marginalized groups and lead to the displacement of the current workforce in the urban transportation system.

Cashing in on green mobility

By all accounts, the modern jeepneys the government is peddling are costly. In some reports, a unit can cost anywhere from 1.6 million to 2.4 million PH pesos (25,780 to 38,520 euro) or up to 3 million PH pesos (48,150 euro). For comparison, the best-selling car in 2023, the Toyota Vios, driven mainly by the middle class, cost 732,000 PH pesos (11,750 euro) up to 1 million PH pesos (16,050 euro) for the top-of-the-line variants. To recuperate this investment, drivers would need to earn 6,000 to 7,000 PH pesos daily (96 to 112 euro), or twice as much as the current daily gross income of 2,500 to 3,000 PH pesos (40 to 48 euro), less the daily operational expenses such as fuel and terminal fees. If the driver is not the jeep’s owner, they still need to pay the operator a fixed amount or “boundary” on top of the operational expenses. Whatever is left becomes their earnings for the day. This ranges from 300 to 400 PH pesos (5 to 6 euro), way below the estimated family living wage of around 1,207 PH pesos (19 euro) based on the computation of IBON Foundation. With this income, they barely make ends meet even after working 10-12 hours behind the wheel. Drivers and operators will have no choice but to demand the LTFRB to raise the base fare for modern jeepneys to generate at least a livable income. Without significant wage increases, this will hurt the pockets of the millions who depend daily on them to get to work or school. Some estimates peg the fare increase as high as 34 PH pesos (0.55 euro) or nearly three times the current fare.

The government is offering a meager subsidy of 160,000 to 260,000 PH pesos (2,600 to 4,200 euro), constituting only 10-15 percent of the total unit cost. A cooperative or corporation must have a fleet of at least 15 units to obtain a franchise to operate a route. For such a multi-million investment, the financial aid will barely make a dent and push them further into debt with private or government-led lending schemes. The wealthy are the only entities able to purchase one or more units under the required cooperative or corporation scheme. This effectively hands the transport sector to the usual suspects – big business.

Since 2017, or the year the PTMP began, the Aboitiz Group has kept its eye on the modernization of jeepneys as one of the entry points into the electric transport business. The Ayala Group and San Miguel Corporation have also entered the electric mobility business by importing, manufacturing parts and assembly, and building of charging stations.

The government’s preference for Chinese mini-bus manufacturers also boggles the mind of Filipinos as there are local jeepney manufacturers that can comply with the required standards without losing the iconic jeepney look for a much lower price of less than 1 million PH pesos (16,000 euro). It was not until 2023 that the LTFRB took consideration following widespread clamor from the public. Even then, local manufacturers find government support lacking. Meanwhile, the car industry has seen a 29 percent increase in sales of cars from last year. This prompts the question of sustainability as the motive behind forcing the jeeps to transition while allowing the automobile industry to rake in profits and increase the already congested roads with more private cars.

The fight for a just transport sector

If there is anything clear about the PTMP, it is that it is not just. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO) definition, “a Just Transition means greening the economy in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities and leaving no one behind.” With the PTMP, the government is implementing wholesale abandonment of a sector that includes tens of thousands of drivers, small operators, and millions of people in the name of “green energy” and “climate change mitigation.”

The intersectionality of environmental and social justice should be noticed. The current dismal state of the transport sector, the impoverishment of jeepney drivers and its patrons, even without the modernization program, has resulted from decades of government neglect, anti-people, and capitalist-friendly policies such as low wages, privatization, and oil deregulation. The same government is now adamant in asking the masses to pay the price for “modernization.”

Jeepney drivers have been evident in saying that they are not against modernization, and they are not against the environment. However, the transition to greener transportation should be just and sustainable. The burden of transition should not be carried by drivers alone. All stakeholders need to share it equitably. The masses need a service-oriented and affordable public transportation, not a profit-oriented and market-based one.

The road to just transition is long, but the jeepney drivers are not ready to give up the fight. Months into the modernization program, the transport workers, human rights, and climate justice activists continue to make a firm stand in challenging the dominant narrative surrounding the PTMP. The masses’ primary mode of public transportation is in danger of being fully captured by big players and conglomerates in the guise of modernization. “We are much more than them. We will continue to fight for our rights,” said the old jeepney driver, weary but resolute in his conviction that they stand on the side of the people and, ultimately, the planet.