Share

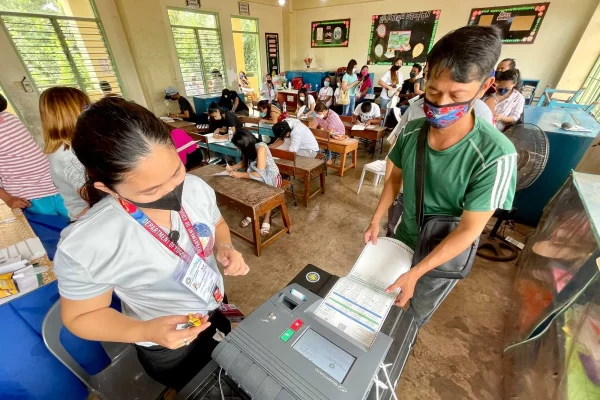

Midterm elections in the Philippines suggest that dissatisfaction is growing — but largely benefits former President Rodrigo Duterte

Inside a rusting file cabinet belonging to a federation of small farmers living on Sicogon, a small island in the Philippines, are four letters that may offer more insight into the results of the country’s recent midterm elections than much of the other data likely to be cited by commentators in the coming days. In these heartfelt appeals, the farmers plead with then-President Rodrigo Duterte to help them in their fight against one of Asia’s biggest conglomerates, Ayala Corporation, over 335 hectares of land long designated by the government for redistribution to them.

Trying to convince Duterte that their cause is just, Sicogon’s farmers first share the story of their struggle, described by some as “a microcosm of the broader struggle between ordinary people and land-hungry giant corporations”. They recount how, after a powerful typhoon destroyed nearly all their houses in 2013, Ayala ordered its guards to bar them from reconstructing their houses and prevent them from accessing relief — only to then offer the farmers some cash and a house on the mainland if they agreed to leave the island forever.

But what happened next is what many on Sicogon remember with even more bitterness. When they refused to give in to Ayala, the farmers write, senior officials from then-President Benigno Aquino III’s administration, many of whom were leading figures in the Liberal Party, met with them repeatedly, claiming to have their best interests at heart. In the end, however, they pressured the farmers into effectively surrendering to Ayala, forcing them to agree to a compromise deal they did not want to sign.

In a follow-up letter to one of Duterte’s officials, the farmers address a familiar concern that has resurfaced in recent months: “We supported President Duterte because we were deceived, betrayed, and sold out to the corporations by the dilawan”, they write, using a term commonly used to refer to Aquino’s party and allies, meaning “yellow”, after the party’s colour.

A Show of Force by Duterte, Signs of Life from the Centre

Although the final results of the Philippine midterm elections held last Monday are unlikely to be known soon, at least two crucial developments can be observed — ones we might better grasp by referring to what Sicogon’s farmers have been saying.

First, despite being deprived of the advantages of incumbency — indeed, despite being the target of a concerted offensive by the incumbent — candidates supportive of or loyal to former President Rodrigo Duterte seemed to have done much better than many expected relative to the candidates belonging to current President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’ slate. This suggests fast-growing popular dissatisfaction with Marcos Jr.’s government — and moreover, that large sections of the public are expressing this dissatisfaction through support for a rival authoritarian-populist project espoused by Duterte and his daughter incumbent, Vice President Sara Duterte.

Second, the political camp denounced by Sicogon’s farmers — that of Aquino and other anti-Marcos/Duterte liberals or moderates who oppose dictatorships but who also do not advocate for socialism — defied extremely bleak expectations and showed signs of life, if not resurgence. But with only two winning Senatorial candidates from their ranks (compared to five from the Marcos coalition and five from Duterte’s camp, they still remain weaker vis-à-vis the other forces on the political stage, and they still likely fared worse this year than in elections during much of the period before Duterte’s entry onto the national stage in 2016, when they regularly fielded bigger slates and frequently dominated the polls.

Moreover, even their success can still be read as a measure of their opponents’ enduring strength (and of their own vulnerability). After all, their winning senatorial candidates felt compelled to avoid antagonizing Duterte’s supporters by refusing to categorically say they would vote for Sara Duterte’s impeachment if they won — while simultaneously trying to avoid the ire of Marcos Jr.’s supporters by saying they should not even be considered part of the “opposition”.

This indicates that while part of the growing public discontent at the Marcos Jr. administration is being captured by “centrists” (if we may use this term with caveats), this part is still currently very small relative to the part being captured by pro-Duterte forces, especially if we consider this in proportion to this camp’s immense clout, resources, and sway.

Thus, the midterm election results suggest that, in the emerging and escalating three-way fight between the country’s dominant political forces — between the contending illiberal or authoritarian-populist projects of Marcos Jr. and Duterte, on one hand, and the fight for leadership of the opposition to Marcos Jr. between pro-Duterte forces and anti-Duterte centrists on the other — it would seem that Marcos Jr.’s side is on the ropes, anti-Duterte centrists are down but not out, while Duterte’s camp stands strong, ready to knock out the other combatants at the right moment. How did we get here?

Old Debate, Unheard Voices

Struggling to make sense of Duterte’s staying power and the liberals’ continuing weakness, many observers will likely point once again to the vulnerability of the masses to “disinformation”, to their unrestrained ignorance, or to their irrational desire for strong men. In short, they will continue to suggest that there is something deeply wrong with the electorate. Far from Duterte’s stronghold in Mindanao and deviating from the archetypal Duterte supporters, the small farmers of Sicogon suggest an altogether different (if still only partial) explanation.

To be clear, these farmers are not at all representative of the electorate. But neither is their experience unique. Hence, their documented opinions — expressed spontaneously without being prompted by researchers — can still potentially give us insight into ordinary people’s changing attitudes and behaviour in recent years.

According to the famers, many like them embraced Duterte and turned against the dilawan because, in their own words, they were “betrayed” and “sold out to the corporations” by the latter. “Fake news” may well have played a role, along with other factors; the full explanation is likely to be more complex. But from the perspective of these farmers, their own direct experience with anti-Duterte liberals could not be excluded from that explanation. The problem, they also thereby suggest, is not with the masses who are always blamed for making the “wrong” choices during elections — but with Duterte’s rivals, who are rarely called out for their own actions.

But why have so many voters refused to move on and forgive centrists despite living through the terms of both Duterte and Marcos? Once again, the experience of Sicogon’s farmers may be instructive here. Since 2014, when Aquino officials pressured them to yield to Ayala, no one has reached out to them — not even to acknowledge the harm that was done. There has been no apology, no expression of regret. Not even a meaningful change in their party’s programme or policy positions.

But perhaps what wounded them more than the lack of contrition was what came next. While Sicogon’s farmers endured heat and thirst as Ayala used up the island’s water to fill their resort’s infinity pools, they heard anti-Duterte moderates endlessly warn of the grave dangers Duterte posed to democracy, ignoring their daily problems. While the farmers ate and defecated in the dark, as their houses remained cut off from the grid while Ayala’s hotel rooms sparkled at night, anti-Marcos campaigners kept talking to them about the importance of joy and hope. All along, liberals refused to say what many of Sicogon’s farmers were waiting to hear: the actual steps they would take to rein in the billionaires swallowing their land and draining their water. There have been some gestures of goodwill, to be sure — free college education, more attention to agriculture, and so on — but nothing that would hurt or be opposed by large corporations, such as real land redistribution or significant wage increases. Instead of concrete steps to ease the burdens of those on the margins, vague promises.

In lieu of an apology, the contrived positivity of the privileged; instead of saying “sorry”, indifference — even callousness. Is it all that surprising, then, that so many voters have refused to forgive and still want to give the “greater evil” more chances instead?

A Revolt from Below?

Why the country’s centrists have not made a break with the past despite repeated defeats is a crucial question that deserves further probing. But whatever the reasons, the centre’s apparent inability to regain more ground coupled with Duterte’s enduring strength is unlikely to be favourable for the country’s progressive movement, which also showed hopeful signs of reinvigoration in these elections but remains as if not more marginalized than ever, unable even to countenance forming a united front against both the centre and the right, as progressives in other countries have done.

At the same time, however, if voters are indeed refusing to return to the liberals’ camp because they have come to see, from their own lived experience, that this camp can no longer represent them, then the Philippines may be entering a new chapter in its political development — one which may open up rare opportunities for the progressive movement.

Instead of being forever mired in ignorance, as so many commentators assume, small farmers and workers may in fact be figuring things out for themselves — part of the messy, non-linear and protracted process by which subordinated groups attempt to detach themselves from the grip of the dominant ideology and try to emancipate themselves.

The problem, of course, is that, for now at least, subordinated groups’ struggle to learn from their own experience and educate themselves remains blunted and stunted.

Prevented from acquiring alternative critical frameworks required to make sense of their subordination — due in part to the Left’s own crisis and inability to reach them — many among the oppressed cannot yet see that their emancipation requires more than simply changing the regime in power. Consequently, their anger also remains prone to being hijacked by rival demagogues, each intent on channelling their energies into intra-elite skirmishes over how best to change everything in order for everything to remain the same. The result could be endless rounds of conflict in the years ahead as the oppressed turn away from the centre and embrace different factions of the right only to swing back to the centre then turn away from them again.

But this, too, may be transitory.

Even now, there are indications that Sicogon’s farmers are yearning for alternatives to the all three forces currently dominating the political stage. Indeed, in the 2022 elections, while most voters in two of Sicogon’s three villages went for Marcos-Duterte — making these villages one of the very few places in one of the liberals’ strongest bailiwicks where the liberals’ candidates lost — a surprisingly sizable number voted for Leody de Guzman and Walden Bello, the first openly socialist presidential candidates in Philippine history, making Sicogon one of the very few places in the country where progressives placed third in the final ranking despite possessing significantly smaller resources than the frontrunners. This could not have happened had progressives not been painstakingly organizing on the ground in Sicogon for years, unaligned with Duterte but also unwilling to do the liberals’ work for them.

This suggests that whether more of Sicogon’s farmers and others like them will embrace the Left in the coming years instead of vacillating between Right and centre depends on one thing, among many others: that socialists, instead of trying to substitute themselves for liberals or siding with one elite faction against another, assert their own identity, build up their own autonomous pole, and become more capable of being present for the oppressed in their continuing self-education and struggle for liberation.

Herbert Docena is a teacher, researcher, and organizer in the Philippines. A member of Partido Sosyalista, he writes here in a personal capacity.