Share

Photo by Malaysiakini

The results of Malaysia’s November 2022 general elections evoked mixed reactions nationwide. Opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim of Pakatan Harapan (Alliance of Hope), who presented himself as a reformist firebrand, formed a government in coalition with Zahid Hamidi, leader of the former dominant UMNO-BN (United Malays National Organisation-Barisan Nasional, National Front). Zahid’s repressive track record raised concerns within civil society, while others remained cautiously optimistic.

The Anwar administration inherited a society still grappling with the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. In the previous administration, anti-migrant and anti-refugee sentiments surged, fueled by rising ethno-religious nationalism. The current government has done little to alleviate these sentiments amid ongoing economic a

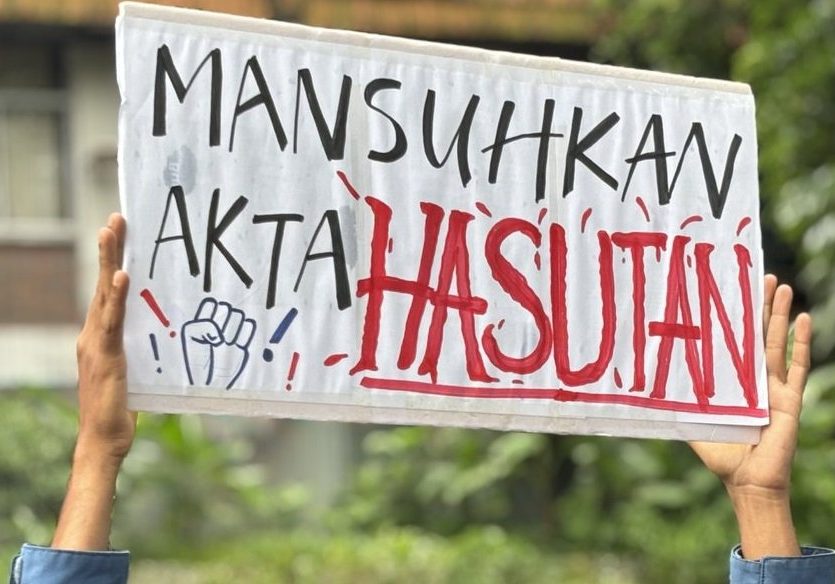

nxiety and has maintained restrictive immigration policies. Persistent pressure from the political far right has led to a highly reactionary stance in government. This stance was most prominently displayed in the December 2023 “Mini Dhaka raids,” where security forces in Kuala Lumpur targeted a neighborhood, arresting migrants for “becoming increasingly bold and behaving like locals.” Recently, the administration faced backlash over proposed citizenship amendments that would end automatic citizenship for foundlings and abandoned children. While the Home Ministry has been quick to commend itself for granting citizenship to children born to Malaysian mothers, civil society swiftly condemned the Minister’s conditions for granting citizenship to indigenous individuals considered “stateless.”

Beyond immigration and citizenship, the Anwar government has faced strong criticism for its handling of corruption cases involving its coalition partners, particularly those within UMNO. The first erosion of judicial impartiality and separation of powers occurred with the High Court’s decision on 4 September 2023, to grant Zahid Hamidi, UMNO president and current deputy prime minister, a discharge not amounting to acquittal of his 47 corruption-related charges. This verdict indirectly signaled the Anwar administration’s intent to drop the charges, seemingly to stabilize the coalition and exonerate a key ally’s leader. It also ignited intense debates about the separation of powers in Malaysia, particularly between the executive and judiciary. The second, and perhaps most egregious, instance was the partial pardon of former prime minister and then-UMNO President Najib Razak for his involvement in the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) corruption scandal. The outcomes of these two cases, along with charges against current opposition leaders, have raised questions about the administration’s use of state power and the judiciary to serve its own narrow interests and ensure political survival.

Progress in women’s rights has been made over the past two years. After over two decades of lobbying by women’s rights organizations, the Anti-Sexual Harassment Act was finally passed in July 2022 under the Ismail Sabri administration. The Public Service Department (PSD) recently established a tribunal as “an alternative platform to improve the legal system and the handling of sexual harassment complaints.” Additionally, an anti-stalking law took effect on 31 May 2023, providing much-needed social protection against gender-based harassment and physical violations. As of December 2023, the police have reported several cases filed under this law.

Another positive development is the passage of an amendment to the Trade Union Bill, aiming to “abolish restrictions on the formation of trade unions based on specific establishment or similarity in trade, occupation or industry.” The law was passed after the necessary votes were passed in the Dewan Rakyat and Senate. This move ends the state-backed monopoly of the Malaysian Trade Union Congress, which has long been the only recognized non-governmental body handling labor affairs. While this development is a positive step, over half a century of labor repression has left trade union consciousness very low, requiring substantial rebuilding effort.

Conflicting Signals on Socio-Environmental Policies in Malaysia

When the Anwar-led coalition came to power, both the public and civil society held low expectations that his administration would pursue the same neoliberal, market-driven approach to development and environmental policy as previous governments. During Pakatan Harapan’s previous tenure from 2018 to 2020, far less had changed than many had hoped amid the euphoria of their historic victory. Their manifesto’s promise to increase renewable energy use, “accelerate adaptation work,” and enhance the welfare and rights of indigenous peoples fell far short in the eyes of many activists. The ministry responsible for the environment has implicitly enabled, rather than restrained, the adverse effects of rapid development. Despite the mounting environmental costs to ordinary Malaysians, the Environment Minister has remained silent on massive developments in Penang, Sarawak, and Pahang. These projects, including land reclamation and hydropower dams, have significantly degraded the environment.

One clear example of this skewed prioritization is the resistance by farmers and fisherfolk to government policies and construction efforts. A particularly high-profile case involves the fisherfolk of the Penang Tolak Tambak (Penang against Reclamation) movement. Their persistent pressure has successfully forced a nearly 50 percent scaleback of the Penang South Island project in May 2023. The movement has affirmed their desire for the entire project to be scrapped, as the project would still endanger their livelihoods and destroy marine ecosystems. Peasant struggles have intensified due to global shifts in food prices following the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and increasing protectionism worldwide. In July 2023, about 100 farmers and fisherfolk protested outside of Parliament, calling on the government to take more decisive action to protect their rights as producers and prioritize national food security. Farmers have also protested evictions to make way for unnecessary developments in Kedah and the drop in paddy prices despite the rise in processed rice and food prices. These protests and confrontations with the police have led to instances of physical violence and intimidation, with members of the Socialist Party of Malaysia sustaining injuries and facing arrests in their support of these peasant struggles.

A key policy initiative from the current administration is the National Energy Transition Roadmap (NETR), launched on 29 August 2023. While the roadmap addresses goals like net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and job creation, it offers little detail on how these investments will incorporate environmental safeguards or protect Malaysia’s indigenous peoples — many of whom face threats to their livelihoods from land grabs and pollution. This disregard is exemplified by the struggle of indigenous residents in the northern state of Kelantan, who are fighting against the Nenggiri Hydroelectric Dam project to protect their livelihoods and cultural heritage. Despite increasingly severe floods and heatwaves linked to global warming, the Malaysian government has not revised its carbon reduction targets, and the NETR prioritizes industrial development over meaningful reductions in national emissions.

Compounding this lack of serious intervention, Malaysian forests continue to diminish under the Anwar administration, likely dipping below the state’s 50 percent forest cover target. Much of this deforestation is driven by timber and palm oil interests, with the eastern state of Sarawak projected to experience over three-quarters of the forest loss. Empowered by a compliant federal administration, the Sarawak state government has ambitious plans to become an “economic powerhouse” through increased infrastructure and industrial investment, often at the expense of indigenous customary lands and forests. Indigenous organizations like SAVE Rivers struggle against state authorities and businesses that exploit their lands without consent. The recent passage of the Environmental Quality (Amendment) Bill 2025 in the Lower House of Parliament signals some intent to enhance ecosystem protections. Still, whether this government will prioritize environmental and climate justice remains uncertain.

Reflecting on the first year of the Anwar administration, progressive groups in civil society have grown more reserved regarding the reform narratives and election promises of the Pakatan Harapan coalition. Having enjoyed access to ministers — many of whom were former allies from civil society — during 2018 and 2019, these groups have now come to terms with the realities of Malaysia’s capitalist state and its political contradictions. As they continue to advocate for greater social rights and climate justice, they engage with the Anwar administration with cautious skepticism.