Share

Image by NAGKAISA

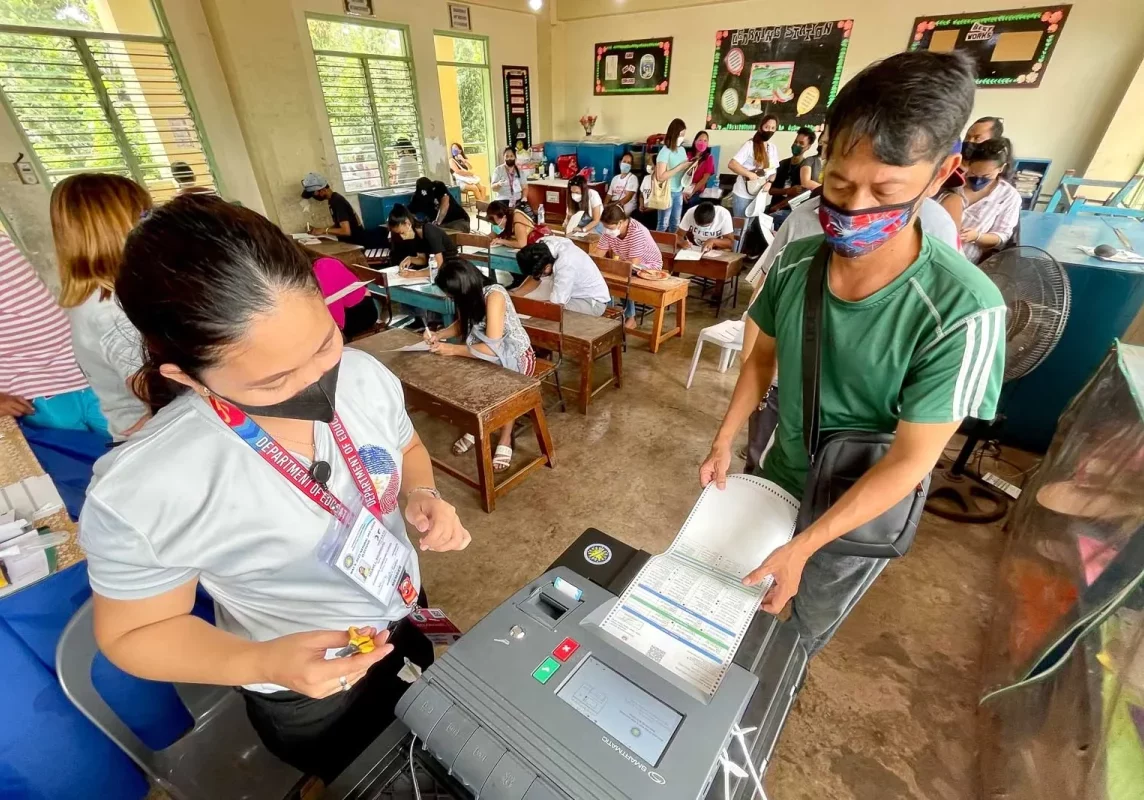

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.‘s first full year in office in 2023 demonstrated both disruption and continuity in governance. While Marcos declared that the war on drugs would continue, his administration has shifted its focus toward prevention rather than the brutal enforcement that marked his predecessor’s approach. This shift is reflected in the reported decline in drug-related deaths, though the issue has not been entirely eradicated. The administration has also acknowledged the plight of innocent victims of the previous drug war, likely mindful of the negative international reputation it garnered and the looming cases filed by the International Criminal Court. However, killings and harassment of political activists persist as the government pursues its pledge to end the armed insurgency. Marcos has visibly realigned the Philippines toward the United States and distanced it from China, signaling a notable foreign policy shift. Yet, the administration’s adherence to neoliberal policies continues to undermine the lives and livelihoods of ordinary Filipinos.

The plight of the working class

The cost-of-living crisis that emerged as the pandemic health emergency subsided has persisted, fueling organized labor’s demands for wage increases. Inflation peaked at 8.7 percent in January 2023 and gradually declined to 3.9 percent by December. Despite strong opposition from employers, the push for salary adjustments gained significant public support. Consequently, wage boards in all regions approved minimum wage hikes from the second half of 2023 through the early months of 2024. This followed a previous round of minimum wage adjustments in nearly all regions during 2022.

Despite two years of minimum wage hikes, wages have effectively eroded by amounts ranging from 73 to 114 PH pesos, depending on the region, according to the group Partido Manggagawa. Meanwhile, computations by the Trade Union Confederation of the Philippines show that minimum wage earners fall below the government’s poverty threshold in all regions except Metro Manila — and only marginally exceed it there. As a result, the majority of workers remain part of the working poor. Government data further indicate that real wages have stagnated over the past two decades, despite robust economic growth and rising labor productivity. While the economic pie has grown, labor’s share has remained unchanged. This persistent income and jobs crisis fuels worker discontent and may partly explain the dips in the administration’s approval ratings in certain instances.

In response, organized labor demanded a 150 PH peso-salary adjustment, framing it as a wage recovery rather than a wage hike. However, the decline of unions has weakened the labor movement, leaving it unable to push for this demand through industrial strikes—a traditional tactic used a generation ago. However, intramurals within the political class have created an opportunity for a legislated salary increase. The Senate expedited the passage of a 100 PH peso minimum wage hike bill while delaying action on a proposal to amend the Constitution. This has increased pressure on the House of Representatives — whose leadership is widely suspected of spearheading the charter change initiative — to pass its own version.

While formal sector workers grapple with diminished purchasing power, informal workers face economic hardships exacerbated by inflation and job insecurity. Jeepney drivers, who operate the Philippines’ most prevalent form of public transportation, have been striving to preserve their livelihoods amid the government’s Public Utility Vehicle Modernization Program (PUVMP).

Initiated in 2017 under former President Duterte, the PUVMP aims to replace traditional jeepneys with modern, fuel-efficient minibuses to reduce emissions and improve safety standards. However, many drivers and operators view the program as anti-poor, citing the high costs of new vehicles and the requirement to form cooperatives as significant barriers. This resistance has led to numerous transport strikes and protests over the years, highlighting the tension between modernization efforts and the economic realities of those in the informal transport sector.

In 2023, the enforcement of the phase of the PUVMP requiring the consolidation of informal jeepney owners — referred to as operators — into cooperatives triggered several strikes, prompting repeated extensions of the deadline. A final deadline looms on the eve of May Day 2024, threatening the livelihoods of approximately 150,000 informal transport workers. This estimate, conservatively based on one operator and one driver for each of the 75,000 jeepneys yet to consolidate, was released by the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) in 2023. The International Labour Organization (ILO) guidelines emphasize the importance of social dialogue as a core element of a just transition. Still, such dialogue has been notably absent in implementing the modernization program. This is particularly ironic given that the Philippines previously participated in an ILO pilot capacity-building project on just transition.

The jeepney modernization program highlights the government’s approach to climate change mitigation, which often overlooks affected groups in favor of private business interests. With each modern jeepney costing up to 3 million PH pesos per unit, it is evident who benefits from this program—and it’s not the ordinary jeepney drivers.

The state of climate action

In 2023, the Philippines recorded its largest climate-related expenditure, amounting to 453.11 billion PH pesos, an increase of over 50 percent from the previous year. Additionally, the Asian Development Bank approved a 200 million US dollar loan, complementing other climate finance agreements with Agence Française de Développement, the Green Climate Fund, and the World Bank. These loans are intended to support projects aimed at scaling up climate adaptation, mitigation, and disaster resilience. However, critics argue that such financing fosters debt dependency and fails to align with climate and economic justice principles.

The government has demonstrated an inconsistent approach to addressing climate change. On one hand, it has allocated significant funds to local government units to enhance disaster and climate resiliency at the community level. On the other hand, it has approved reclamation and infrastructure projects that have disastrous socio-ecological impacts on affected communities. For instance, the deforestation and displacement caused by the New Manila International Airport construction contributed to severe flooding in 17 Bulacan towns north of Metro Manila during Typhoon Doksuri in July 2023.

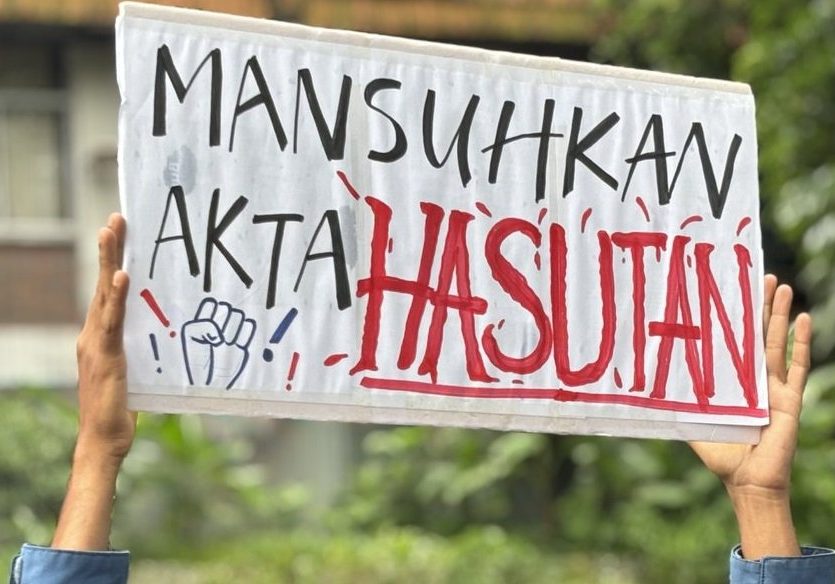

Environmental degradation in the Philippines is frequently linked to human rights violations. In September 2023, environmental activists Jonila Castro and Jhed Tamano, who were opposing reclamation projects, were abducted by state forces. For the tenth straight year, watchdog Global Witness named the Philippines the deadliest Asian country for land and environmental defenders.

The situation of agriculture and farmers

Marcos famously promised to bring down rice prices to 20 PH pesos per kilo. Yet, the staple food of Filipinos currently sells at a retail price of around 50 PH pesos per kilo. Subsidized rice is sold at 39 PH pesos per kilo. Still, many poor Filipinos complain that Kadiwa stores — government-operated outlets for selling agricultural products at below-market prices — are nowhere to be found. The wholesale price of rice rose by 30 percent in March 2024. Projections indicate that prices will remain elevated due to high costs in the international market and the impact of El Niño on local agriculture. As the world’s largest importer of rice, the Philippines remains subject to the vagaries of both climate change and the international market.

The government’s failure to control rice prices and prevent a food crisis for the poorest Filipinos highlights the impact of neoliberal reforms. The National Food Authority, tasked with buying rice from farmers at above-market rates, has been weakened, leading to food insecurity and high prices. Food inflation accounts for half of total price rises. The country imports basic foodstuffs like garlic, onions, beef, chicken, and corn from China, the US, Indonesia, and Thailand.

Despite being an archipelago with abundant seas, the Philippines imports approximately 93 percent of its salt at a cost of around 6 billion PH pesos annually, primarily from Australia and China. Historically, coastal areas such as Parañaque, Las Piñas, Bulacan, and Cavite were major salt producers. However, urbanization has transformed these regions into commercial and residential zones, forcing many informal salt workers to turn to alternative livelihoods due to the lack of government support.

The plight of Filipino farmers mirrors the struggles faced by other marginalized sectors in the Philippines. While various agrarian reform programs since the 1930s sought to placate peasant unrest and redistribute land to rice and corn tenants, many beneficiaries have struggled with the competition of imported products as liberalization accelerated after the 1986 transition from dictatorship to democracy. Consequently, many agrarian reform beneficiaries have lost control of their land to ariendadors or merchants financing farmers’ expenses. The compromised Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program of 1986 was riddled with loopholes that facilitated large-scale land conversion to export zones, mining concessions, real estate, and tourism development. Of the official target of the last agrarian reform measure, one million hectares of the most fertile agricultural land remains in the hands of landlords, including plantations owned by agricultural multinational corporations.

The Philippines is often called an agricultural society, yet in 2023, agricultural output accounted for only 9.4 percent of annual GDP, and employment in farming represented just 24 percent of the total workforce. The pauperization and proletarianization of the agricultural workforce persist, with the average farm size declining from 2.8 hectares in 1980 to 1.3 hectares in 2012—the most recent year with disaggregated data. The majority of farms are now less than one hectare in size. Of the country’s nearly 50 million-strong labor force, approximately 3.7 million farmers own their land, while another 3.7 million are tenants or peasants. The forthcoming results of the 2022 agricultural census may shed light on how these trends have evolved.

With Marcos nearing two years in office, the state of the nation appears grim. Promises of a better life for the people remain unfulfilled, and the administration shows little initiative in addressing mass poverty, worsening inequality, and the climate emergency.